What are drug-resistant infections?

Our collective overuse of antibiotics is causing one of the most urgent global health problems. In this Q&A, we explain what drug-resistant infections are, who is affected and what we can do to stem the rise and spread of drug-resistant infections.

What are drug-resistant infections?

Infections become drug-resistant when the microbes that cause them adapt and change over time, developing the ability to resist the drugs designed to kill them. One of the most common types of drug resistance is antibiotic resistance. In this process bacteria – not humans or animals – become resistant to antibiotics. These bacteria are sometimes called ‘superbugs’.

The result is that many drugs, such as antibiotics, are becoming less effective at treating illnesses. Our overuse of antibiotics in humans, animals and plants is speeding up this process.

Without antibiotics that work, routine surgery like hip replacements, common illnesses like diarrhoea, and minor injuries from accidents, even cuts, could become life-threatening.

Why are drug-resistant infections dangerous?

Drugs like antibiotics are a vital tool for modern medicine, used to prevent and treat infections. As drug-resistant infections are becoming more common, modern medicine as we know it is at risk.

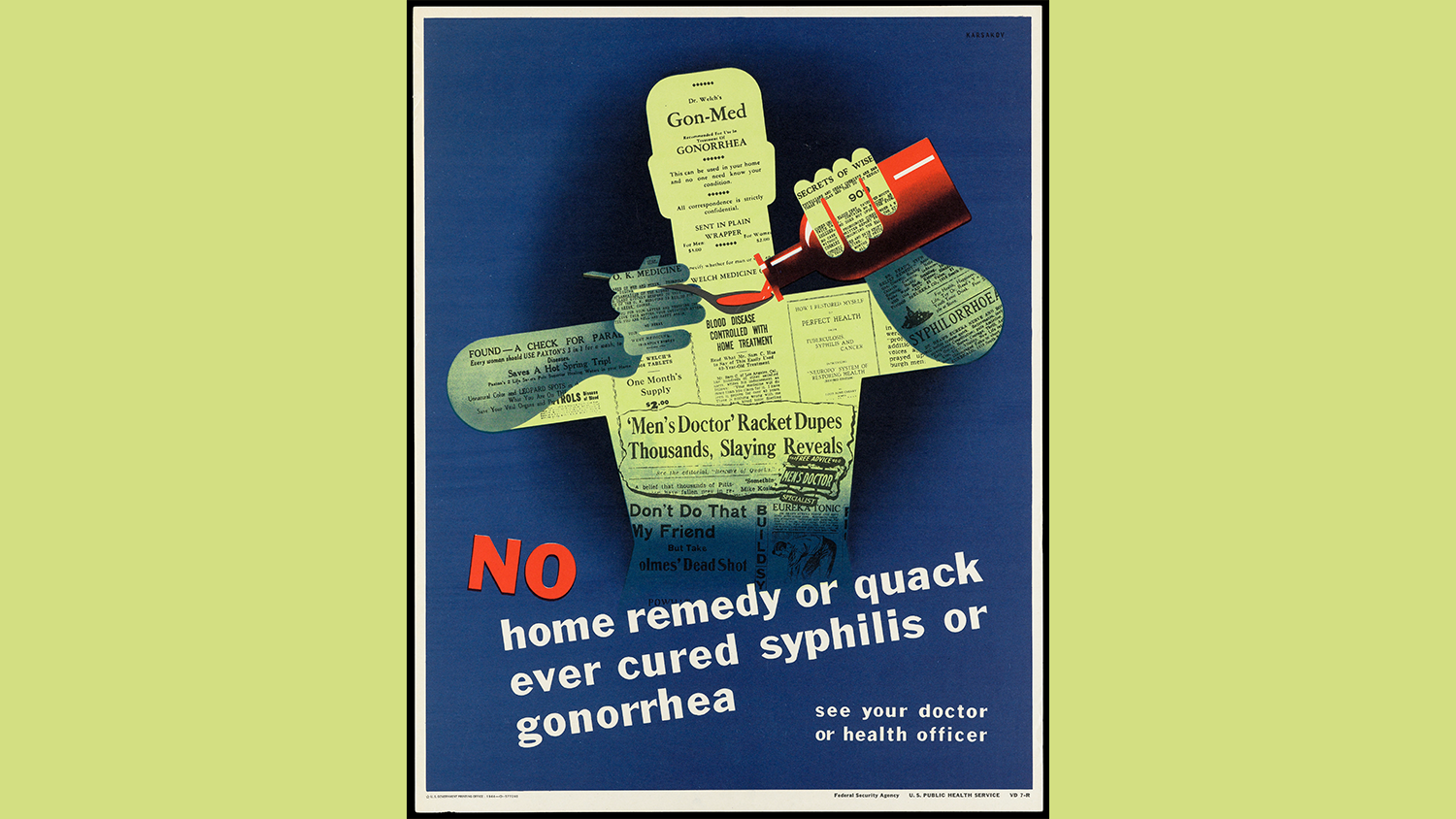

Without effective antibiotics, common infections that were once easily treatable – such as gonorrhoea and urinary tract infections – are becoming untreatable or need lengthy hospital stays.

Routine medical interventions, such as chemotherapy, organ transplants and other surgeries, are becoming less safe because of the infection risk.

Childbirth is also becoming riskier, as without working antibiotics it is more difficult to control infections around the time of birth. This is already a huge problem in countries like India, Pakistan and Nigeria, where thousands of newborn babies die every year because of sepsis that is resistant to antibiotics. Researchers estimate that one in five people who died from drug resistance in 2019 were under the age of five.

Other drugs are at risk of becoming less effective due to resistance, including antifungals, antiviruals and antimalarials. This makes it harder to treat fungal infections, HIV or malaria, for example.

Who is affected by drug-resistant infections?

Drug-resistant infections can affect anyone, anywhere. We are all at risk of infections from drug-resistant bacteria.

Researchers estimate that over 1.2 million people died from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in 2019. This is around 3,500 people on average every day in more than 200 countries and territories.

In some countries, such as India, tuberculosis (TB) continues to be the most dangerous infectious disease. Worldwide, out of 10.6 million people with the illness in 2020-21, over half a million cases were caused by drug-resistant TB. This poses new risks, especially for children who are much more vulnerable to the disease.

Understanding the health burden of drug-resistant infections is challenging because of lack of data and standardised surveillance across different regions and countries. It is possible that many more people are affected than we realise.

How does drug resistance happen?

Like all living things, microbes evolve over time in response to their surroundings. Antibiotic resistance is an example of this evolution, occurring when bacteria change in a way that makes antibiotic substances harmless to them.

They do this in several ways. Some bacteria can ‘neutralise’ the antibiotic before it can do harm. Others have learned to quickly pump the antibiotic out of their cells. And others can change their outer structure so the antibiotic cannot attach to the bacteria and kill them.

The resistant bacteria survive and multiply. If they are passed on to other people, animals or the environment, resistant infections can spread rapidly.

For example, it took only five years for an antibiotic resistant strain of K. pneumoniae to spread globally from the USA, where it was first found in 2003, to Israel in 2005 and then to Italy, Colombia, the United Kingdom and Sweden by 2008.

Why are we seeing more drug-resistant infections?

Drug resistance is a natural phenomenon, but its recent growth is largely driven by human activity.

Our collective overuse of antibiotics in humans, animals and plants is accelerating the development and spread of drug-resistant infections. Unnecessarily exposing bacteria to medicines creates more opportunities for drug resistance to develop and spread.

Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that only half of antibiotics are used correctly.

Antibiotics are used in huge quantities as growth promoters, prophylactics and therapeutic treatments in livestock, fish and crop farming. In some countries, it is thought that 80% of the total consumption of antibiotics is in the animal sector, largely for accelerating growth in healthy animals.

In human healthcare too, antibiotics are widely misused. Of the 150 million prescriptions for antibiotics written by doctors in the USA every year, 50 million were not necessary. In OECD countries, 50% of antibiotics prescribed by general practitioners are thought to be inappropriately used – either not needed, or the wrong antibiotic was prescribed.

In some countries, regulation on antibiotic use is poorly enforced or doesn’t exist at all. People can buy antibiotics over the counter to treat viral infections, instead of bacterial ones.

Although there is an urgent need to limit the inappropriate use of antibiotics, currently more lives are lost because of lack of access to life-saving antibiotics. Globally, almost 6 million people die each year from treatable infectious diseases.

Using antibiotics appropriately – and making them available and affordable where they’re needed – are both important for improving health globally, now and in the future.

When will drug-resistant infections be a problem?

Drug-resistant infections are already a problem.

1.2 million people died from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in 2019. If we don’t act now, this number is projected to rise to 10 million by 2050. This means that globally more people will die because of drug-resistant infections than cancer. Drug-resistant infections will cause six times more deaths than diarrhoeal diseases, measles and cholera combined.

All countries are – and will be increasingly – affected. But the greatest health burden will be in low- and middle-income countries where health systems are not as strong.

Drug-resistant infections could also have wider impacts on livelihoods. Resistant infections can put additional burden on vulnerable people living in poverty. And spread of resistant infections in livestock animals could affect availability of meat and dairy products.

Are drug-resistant infections a global problem?

Yes. In an era of increased mobility and globalisation, microbes cannot be contained within national borders, spreading between people, animals and through environmental channels like water or soil.

Across the world drug resistance is very common. In 2019, close to one in five bacterial infections in OECD countries were resistant to antibiotics. In low- and middle-income countries, resistance is even higher. For example, in India, Brazil and the Russian Federation, 40% to 60% of infections are resistant.

Genes associated with drug-resistant bacteria have even been found in the Arctic Circle and Antarctica, some of the remotest places on earth.

Drug-resistant infections are a threat to global economies and healthcare systems. The World Bank predicts global gross domestic product – the total value of goods and services in one year – could fall by as much as $3.4 trillion by 2050 as a direct result of drug-resistant infections.

Can we stop drug-resistant infections?

We can’t completely stop drug-resistant infections from happening but, by taking action now, we can slow them down.

Drug resistance is a natural evolutionary process. Resistance to antibiotics was recorded even before the first clinical use of penicillin in the 1940s. Since then, resistance to all classes of antibiotics has been discovered.

Although we can’t stop it, we can control the pace of resistance development and spread – for example, through better use of existing antibiotics and the development of new ones.

How can we slow down drug-resistant infections?

As a global problem, drug-resistant infections need a worldwide response.

Better use of existing antibiotics across human healthcare and the animal sector is vital. With limited exposure to antibiotics, bacteria will have fewer opportunities to develop resistance.

Healthcare communities around the world are making concrete efforts in this area. For example, Tanzania is changing the way antibiotics are dispensed through a national network of accredited drug dispensing outlets. South Africa is training hospital pharmacists in antimicrobial stewardship and Ghana uses dance to educate communities about when to take antibiotics. In Nigeria, university researchers are training students to engage with people in local communities about appropriate antimicrobial use.

In Europe, the UK has managed to cut the amount of antibiotics used since 2014, and it is now implementing a five-year action plan to reduce this even further.

Alongside ‘antibiotic stewardship’, we need robust surveillance in all countries and across sectors. This is to better understand the presence and spread of resistance and take actions where and when they are needed.

It is also important to develop new low-cost, fast diagnostics. This will help doctors and pharmacists distinguish between bacterial and viral infections and prescribe the correct medication, in the right dose.

To slow down resistance, we need new antibiotics too. Developing new drugs comes with scientific, economic and regulatory challenges, as it’s a very long and expensive process. For these reasons, no new classes of antibiotics have been approved for use in decades.

Preventing infections is another route for curbing drug resistance. Developing new vaccines, access to clean water, better sanitation and hygiene are effective ways of doing that.

What is the difference between antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial resistance and drug-resistant infections?

Antibiotic resistance is the ability of bacteria to change in a way that makes antibiotics ineffective.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a broader term, which includes antibiotic resistance and other types of drug resistance developed by viruses (such as HIV), fungi (such as Candida) and other microbes.

Drug-resistant infections is a term we use to describe illnesses that have been caused by resistant microbes, resulting in an infection that is much harder – or potentially impossible – to treat.

Wellcome's report Reframing Resistance recommends drug-resistant infections as the term that is most easily understood when communicating with the public.

We’re funding research to better understand what causes and drives infectious diseases to escalate and the solutions to control their impact.

There are currently no open funding opportunities for Infectious Disease. Learn more about the funding we provide.

This article was first published on 9 September 2019

Related content

This Q&A explains what drug-resistant infections are, who is affected and what we can do to stem them.