Wellcome Photography Prize 2021

This year, the Wellcome Photography Prize is exploring the human side of three urgent health challenges: mental health problems, infectious diseases and global heating.

This year, the Wellcome Photography Prize is exploring the human side of three urgent health challenges: mental health problems, infectious diseases and global heating. The prize is now closed for submissions.

Sign up for emails to get the latest news about the Wellcome Photography Prize, including when the 2022 prize will be opening.

The three health challenges affect people of all ages, in all parts of the world – although their effects are not felt equally.

But there is hope. People and communities around the world are coming up with ingenious ways to manage mental health, control the spread of infections, and adapt to the local health risks of global heating. Theirs are the voices we want to show – the inspiring stories that need to be shared.

If you've made a submission to the prize, you can still view your entry.

A high-profile panel of judges from the arts and global health will shortlist and choose the winning images.

Managing Mental Health

All of our minds work differently, and sometimes in ways that can negatively affect us.

There are many ways of managing our mental health – sometimes we can do it by ourselves, and sometimes we benefit from more support to understand our mental health problems, or prevent episodes of an illness that could otherwise hold us back from living the life we want.

Managing Mental Health (single image) examples

Alison, who suffers from depression, is a single mother to Joe, who was diagnosed with autism when he was four. As a full-time carer for her son – who has learning difficulties and frequent fits of rage – Alison’s own mental wellbeing is at risk. As she says, 'it’s so hard to try to be okay all of the time… in front of my boy'. In this image, Alison takes a moment to herself, wiping away tears after dealing with one of Joe’s emotional outbursts.

Placing the camera across the room and using the self-timer, photographer Dora Kovacs captured this sombre self-portrait, meant to portray her experience with depression and anxiety. Kovacs says, 'I found it hard to ask for help, to reach out to my loved ones or a professional therapist. With this photograph I would like to highlight how secluded each of us is, only connected to the real world by social media, by the internet.'

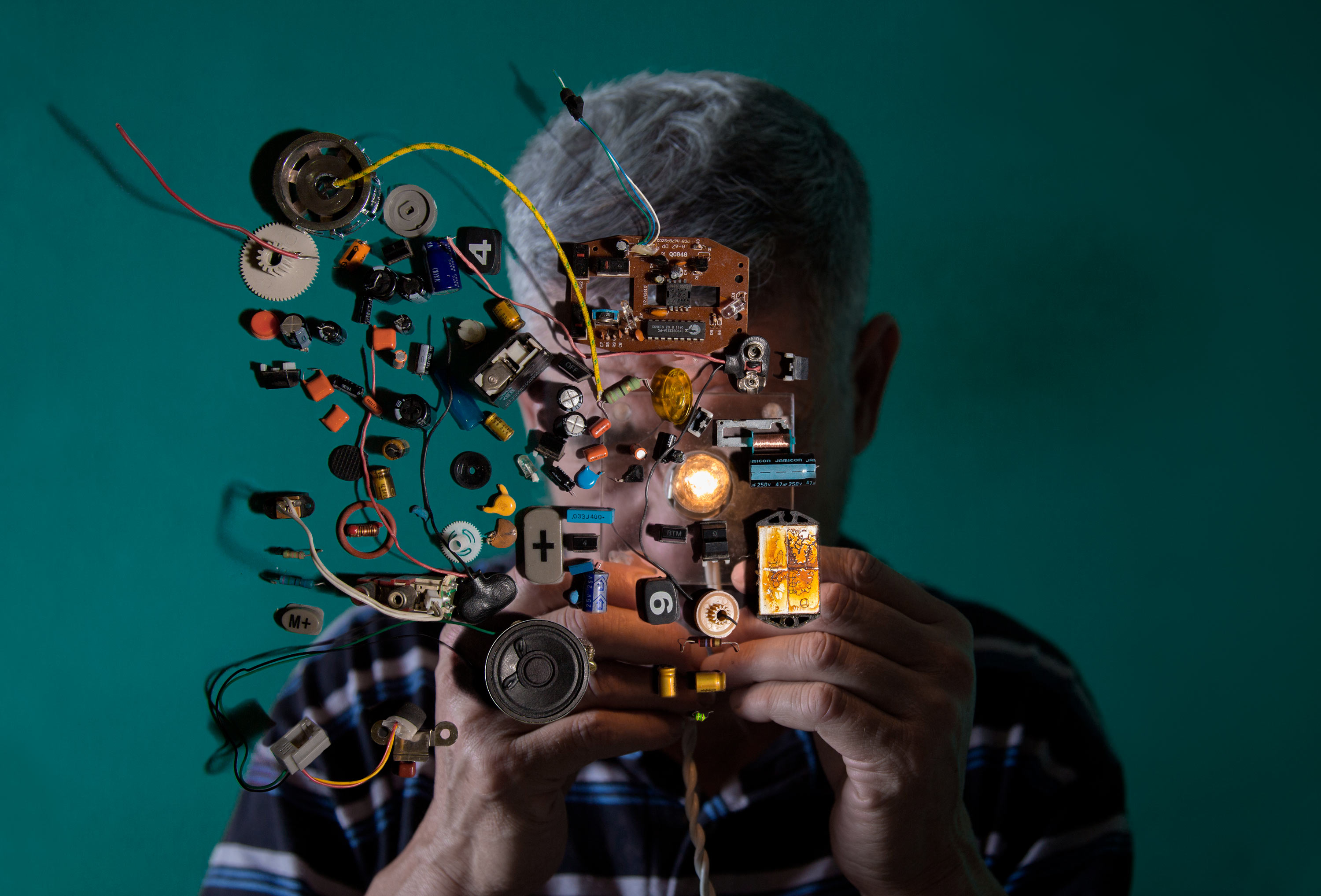

Edmundo, the photographer’s uncle, has lived with schizophrenia from a young age. While a teenager studying for a degree in electronic engineering, Edmundo suffered his first schizophrenic episode, and consequently left school and moved back into his childhood bedroom. Since then, Edmundo has taken non-working electrical devices and transformed them into something new, a practice his niece describes as 'his need to interfere with reality via creativity.'

Managing Mental Health (series) example

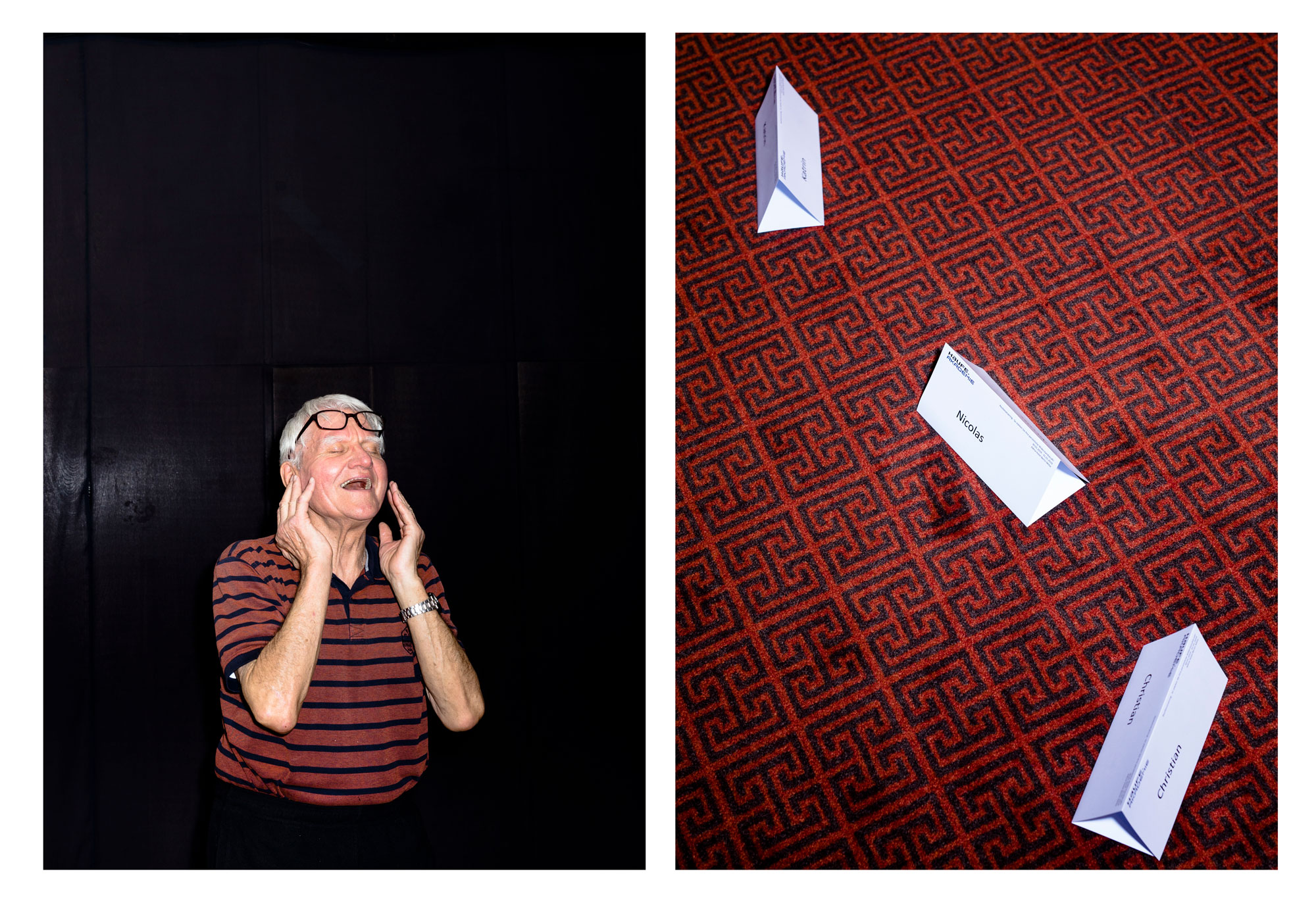

Stelte describes his photographs as 'between documentation and distortion', seemingly staged images that use flash and tight framing to lend a note of unreality and absurdity to his photographs of the group meetings.

About this series

Between winter 2018 and spring 2019, photographer Nils Stelte travelled through Berlin, documenting groups of people in their search for relief from the stresses of urban living. Gathering in forests or hospitals or hotel lobbies, these city-dwellers perform what Stelte calls 'rituals' and 'symbolic acts', ways of combatting and escaping from stress and anxiety.

An older man smiles as he closes his eyes as part of a group exercise in stress relief, the colours and patterns of his shirt recalled in the image on the right, with nametags of the group participants brought into sharp focus.

About this series

Between winter 2018 and spring 2019, photographer Nils Stelte travelled through Berlin, documenting groups of people in their search for relief from the stresses of urban living. Gathering in forests or hospitals or hotel lobbies, these city-dwellers perform what Stelte calls 'rituals' and 'symbolic acts', ways of combatting and escaping from stress and anxiety.

In a splay of limbs and contortions, participants use their bodies to expel stress and anxiety.

About this series

Between winter 2018 and spring 2019, photographer Nils Stelte travelled through Berlin, documenting groups of people in their search for relief from the stresses of urban living. Gathering in forests or hospitals or hotel lobbies, these city-dwellers perform what Stelte calls 'rituals' and 'symbolic acts', ways of combatting and escaping from stress and anxiety.

A man submerges his body in the freezing water, the cool and placid blues and whites of the left image echoing the colours of the Milky Way bars, one of the snacks offered at a group meeting.

About this series

Between winter 2018 and spring 2019, photographer Nils Stelte travelled through Berlin, documenting groups of people in their search for relief from the stresses of urban living. Gathering in forests or hospitals or hotel lobbies, these city-dwellers perform what Stelte calls 'rituals' and 'symbolic acts', ways of combatting and escaping from stress and anxiety.

A group of women link arms while performing one of the 'rituals' designed to alleviate the stress of city living.

About this series

Between winter 2018 and spring 2019, photographer Nils Stelte travelled through Berlin, documenting groups of people in their search for relief from the stresses of urban living. Gathering in forests or hospitals or hotel lobbies, these city-dwellers perform what Stelte calls 'rituals' and 'symbolic acts', ways of combatting and escaping from stress and anxiety.

Fighting Infections

The Covid-19 pandemic is inescapable this year. Its spread has revealed how connected we all are. Everywhere there are now signs to wash hands, wear masks and keep a social distance.

This invisible virus has caused so many deaths and so much disruption. But it is not the only infection that needs to be brought under control. Many communities around the world are fighting other outbreaks or trying to prevent them. Has the focus on Covid-19 helped? Which other stories have been obscured by the pandemic?

Fighting Infections (single image) examples

Photographer Erica Hawkins gets down to eye level with her four-year-old son Jacob to take this image of him in the bath, one of the only places where he finds relief from the small, itchy blisters covering his body – the most recognisable symptom of chickenpox. A common childhood infection, chickenpox is usually mild and complications are rare, although the incessant itchiness is aggravating.

A group of contestants wait backstage at the fourth annual Y+ Beauty Pageant, a contest developed for young people living with HIV in Uganda. The pageant’s mission is to fight the social stigma that is attached to being HIV positive and promote understanding and acceptance.

Tayane, aged 19, cradles her daughter Izabella, who was born with congenital Zika syndrome. The Zika virus, carried by mosquitoes, usually causes mild illness, but can lead to severe birth defects when mothers are infected during pregnancy. Tanaye and Izabella live in Brazil, the epicentre of the Zika outbreak in 2015–16, and Izabella was diagnosed in 2018 with microcephaly and encephalocele – two congenital defects caused by her mother’s Zika infection.

Fighting Infections (series) example

Laura and María, both actresses, share a flat in Lavapiés, spending their days together during the lockdown. Laura, who has been unemployed for a year and spent most of her time at home before the pandemic, says her routine is not that different, except for María’s now-constant presence.

About this series

In her series Confinadas ('Confined'), Spanish photographer Isabel Permuy documents three months of lockdown in the Madrid neighbourhood of Lavapiés. Spain, hit hard by Covid-19, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe in March and April 2020, measures which saw individuals adjusting to the new normal of extended periods of isolation and confinement, in an effort to combat the rapid rise in cases and deaths.

Raquel, aged 45, lost her best friend to Covid-19 and – with restrictions at their peak in Madrid – was not permitted to attend the funeral. She says: 'When the feeling of helplessness passed over me, for not being able to go to the funeral, I started to clean everything, and I have done that ever since.'

About this series

In her series Confinadas ('Confined'), Spanish photographer Isabel Permuy documents three months of lockdown in the Madrid neighbourhood of Lavapiés. Spain, hit hard by Covid-19, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe in March and April 2020, measures which saw individuals adjusting to the new normal of extended periods of isolation and confinement, in an effort to combat the rapid rise in cases and deaths.

'I have a lot of people who care about me and I care about them, so even though I’m home alone I’m not alone mentally,' says Rebeca, aged 76, who passes the quarantine speaking to friends on the phone.

About this series

In her series Confinadas ('Confined'), Spanish photographer Isabel Permuy documents three months of lockdown in the Madrid neighbourhood of Lavapiés. Spain, hit hard by Covid-19, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe in March and April 2020, measures which saw individuals adjusting to the new normal of extended periods of isolation and confinement, in an effort to combat the rapid rise in cases and deaths.

During lockdown, María Jesús celebrated her 80th birthday on her balcony, with applause and chants from her neighbours – affection from a distance.

About this series

In her series Confinadas ('Confined'), Spanish photographer Isabel Permuy documents three months of lockdown in the Madrid neighbourhood of Lavapiés. Spain, hit hard by Covid-19, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe in March and April 2020, measures which saw individuals adjusting to the new normal of extended periods of isolation and confinement, in an effort to combat the rapid rise in cases and deaths.

María works at Madrid’s Reina Sofía Museum, now remotely, and lives with her daughters in the Lavapiés neighbourhood. To ensure her daughters continued their schoolwork while at home, María established schedules and routines, much like other parents forced to readjust to homeschooling during the pandemic.

About this series

In her series Confinadas ('Confined'), Spanish photographer Isabel Permuy documents three months of lockdown in the Madrid neighbourhood of Lavapiés. Spain, hit hard by Covid-19, implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe in March and April 2020, measures which saw individuals adjusting to the new normal of extended periods of isolation and confinement, in an effort to combat the rapid rise in cases and deaths.

Health in a Heating World

Wildfires and extreme weather are the most visible signs of our changing climate, and the risk they pose to life and livelihoods is all too clear. The heat has more insidious ways to harm people’s health, too – in some cities, temperatures regularly reach 50°C, while in the fields, workers struggle to stave off dehydration day after day.

Climate change is a worldwide problem but, until we can stop global heating, it will take local solutions to protect people's health from its harmful effects.

Health in a Heating World (single image) examples

A man paid by the city corporation sprays the streets of Uttara, a 'model town' in the northern suburbs of Dhaka, Bangladesh, that boomed over the past 20 years. Upper-middle-class neighbourhoods are sprayed with anti-mosquito spray more often than the poorer areas of the capital but the residents seem unsure about the regularity of the spraying: some say it is done daily, others once a month.

There is debate as to whether or not the spray has, in fact, any impact on reducing mosquito numbers, with the intention of decreasing the risk for mosquito-borne diseases like Dengue fever.

Pakistan’s flood crisis in 2010 affected the health of millions of residents, as well as the ability to deliver emergency and routine healthcare across the country.

Here, Mueen Ibrahim and his grandfather walk through flood waters back to their family home, which they and their relatives evacuated days before the floods hit. Health risks like decreased access to safe drinking water, threats of waterborne diseases, and damage to hospital facilities are large-scale consequences to flooding, coupled with the consequences for individual families like Mueen and his grandfather’s.

Bangladesh is among the countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Floods, cyclones, droughts and other environmental disasters linked to a heating planet threaten the lives and futures of the country’s more than 160 million people.

In this image, a family mourns atop the ruins of their house, destroyed by 2019 cyclone Fani, one of the most powerful cyclones formed in the Bay of Bengal in the last 20 years.

Health in a Heating World (series) example

The Saravani family has lived in the Sistan and Baluchestan region for more than a century, in the Rige Mouri village. In the past, more than 3,000 people lived in the village, but now only 17 families remain, grappling with the dust and sand caused by high-intensity winds and drought.

About this series

Sistan and Baluchestan, the largest province of Iran, used to be one of the greatest sources of crops in the country, with the region’s Hamun Lake a plentiful water source. Now, because of rapidly rising temperatures, this vast region is an infertile desert, with nothing left for those whose livelihood depended on the lake’s opportunities for fishing, farming and animal husbandry. More than a quarter of the region’s population has fled to other areas of Iran, while those remaining grapple with drought, famine and unemployment.

Along with the environmental consequences of climate change, societal issues like unemployment, poverty and addiction have ravaged this region of Iran. Hoveida, age 30, lives next to the Zaha dam; recently full of water, the dam is dried up, with Hoveida collecting the urban sewage and garbage that now gathers in the dam. He would like to get into rehab but doesn’t think it’s possible.

About this series

Sistan and Baluchestan, the largest province of Iran, used to be one of the greatest sources of crops in the country, with the region’s Hamun Lake a plentiful water source. Now, because of rapidly rising temperatures, this vast region is an infertile desert, with nothing left for those whose livelihood depended on the lake’s opportunities for fishing, farming and animal husbandry. More than a quarter of the region’s population has fled to other areas of Iran, while those remaining grapple with drought, famine and unemployment.

Nabi Sarani, 63, watches over the few sheep that remain after this year’s severe drought. A livestock holder and famer, Sarani depends on fresh water to irrigate his crops and care for his animals.

About this series

Sistan and Baluchestan, the largest province of Iran, used to be one of the greatest sources of crops in the country, with the region’s Hamun Lake a plentiful water source. Now, because of rapidly rising temperatures, this vast region is an infertile desert, with nothing left for those whose livelihood depended on the lake’s opportunities for fishing, farming and animal husbandry. More than a quarter of the region’s population has fled to other areas of Iran, while those remaining grapple with drought, famine and unemployment.

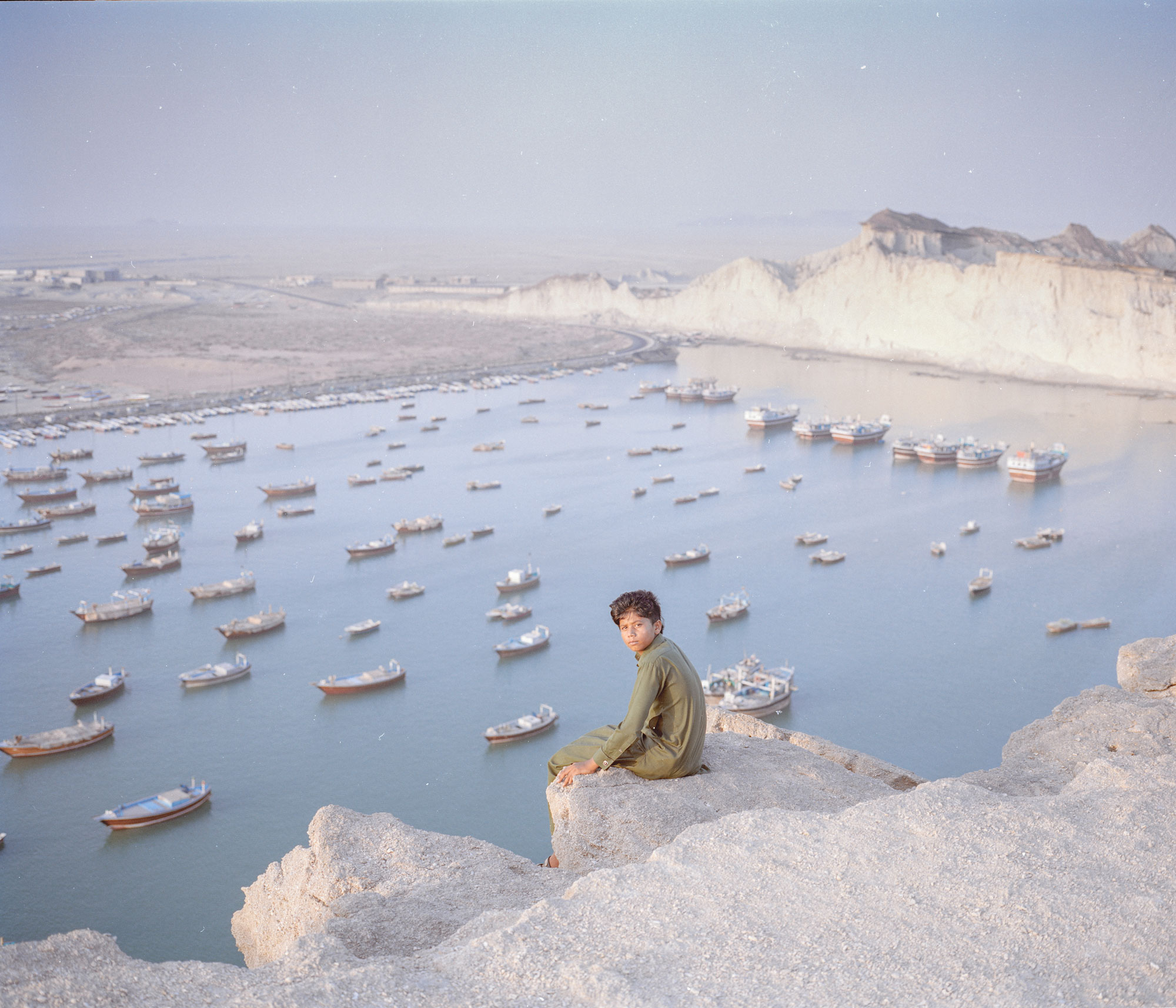

Thirteen-year-old Hossein is from Chabahar, a seaport in the southeastern area of Sistan and Baluchestan province. Despite Chabahar’s proximity to the sea, many of the area’s residents lack access to clean drinking water because they live in poverty.

About this series

Sistan and Baluchestan, the largest province of Iran, used to be one of the greatest sources of crops in the country, with the region’s Hamun Lake a plentiful water source. Now, because of rapidly rising temperatures, this vast region is an infertile desert, with nothing left for those whose livelihood depended on the lake’s opportunities for fishing, farming and animal husbandry. More than a quarter of the region’s population has fled to other areas of Iran, while those remaining grapple with drought, famine and unemployment.

Tamin village, where 60-year-old Abdullah lives, had many healthy trees, thriving despite the drought that affects the area. Due to a beetle infestation, however, believed to be caused by the drought, a strong toxic pesticide was sprayed over the trees, causing them to dry up and lose their fruit.

About this series

Sistan and Baluchestan, the largest province of Iran, used to be one of the greatest sources of crops in the country, with the region’s Hamun Lake a plentiful water source. Now, because of rapidly rising temperatures, this vast region is an infertile desert, with nothing left for those whose livelihood depended on the lake’s opportunities for fishing, farming and animal husbandry. More than a quarter of the region’s population has fled to other areas of Iran, while those remaining grapple with drought, famine and unemployment.

The finalists of each category will receive £1,000.

Our single image and series winners will each receive £10,000.

Prizes will be presented at an awards ceremony in summer 2021. The winning and shortlisted entries will then go on show at a public exhibition in London.

Read about the entry conditions and judging criteria, and the terms and conditions for the Wellcome Photography Prize 2021.

You can also read our frequently asked questions.

Our privacy statement explains how, and on what legal basis, we collect, store, and use your personal information.

If you would like to know more about the prize

- Read our frequently asked questions

- Email PhotoPrize@wellcome.org

For media enquiries

- Call +44 (0)20 7611 8866

- Email media.office@wellcome.org

The Wellcome Photography Prize 2021 is supported by Spectrum.

Hayleigh was quite deflated at this point, two months into lockdown, and washing her hair felt like a huge task.