When will the world be vaccinated against Covid-19?

How should the global community prioritise the distribution of Covid-19 vaccines to give us the best chance of ending the pandemic and saving lives?

The global effort to find vaccines for Covid-19 has been incredibly successful, with multiple vaccines demonstrating high efficacy. There have been more than 4 billion vaccine doses distributed across 180 countries already.

But it will take several years to manufacture and distribute enough vaccine doses to cover the almost eight billion people on Earth. We are already seeing huge inequalities in vaccine access with more than 50% of people vaccinated in high-income countries compared with only 1% of people in low-income countries.

Current estimates are that it will take well into 2023-24 for everyone who needs a vaccine to receive one.

So how should the global community prioritise the distribution of vaccines to give us the best chance of ending the pandemic and saving lives?

Decisions on how to prioritise vaccine doses must balance the needs in each country, and the world.

Covid-19 vaccines will have the biggest impact on reducing strain on our health services, and reducing restrictions on other parts of society, if we prioritise using them to protect the most vulnerable in all countries.

It’s a bit like if you had a family gathering of nine relatives, but you only have three doses of a vaccine now, you’re expecting three more in six months and three more next year. You’d have to decide who to vaccinate first, second and third.

You would probably give it to your grandparents first because they would be most at risk of dying from Covid-19.

Once they’ve had it, you could see them with much less risk of transmitting the virus to them or them becoming ill.

But what if you had a sibling with asthma? Or parents working and travelling outside the home, who are more likely to bring an infection into the house from outside?

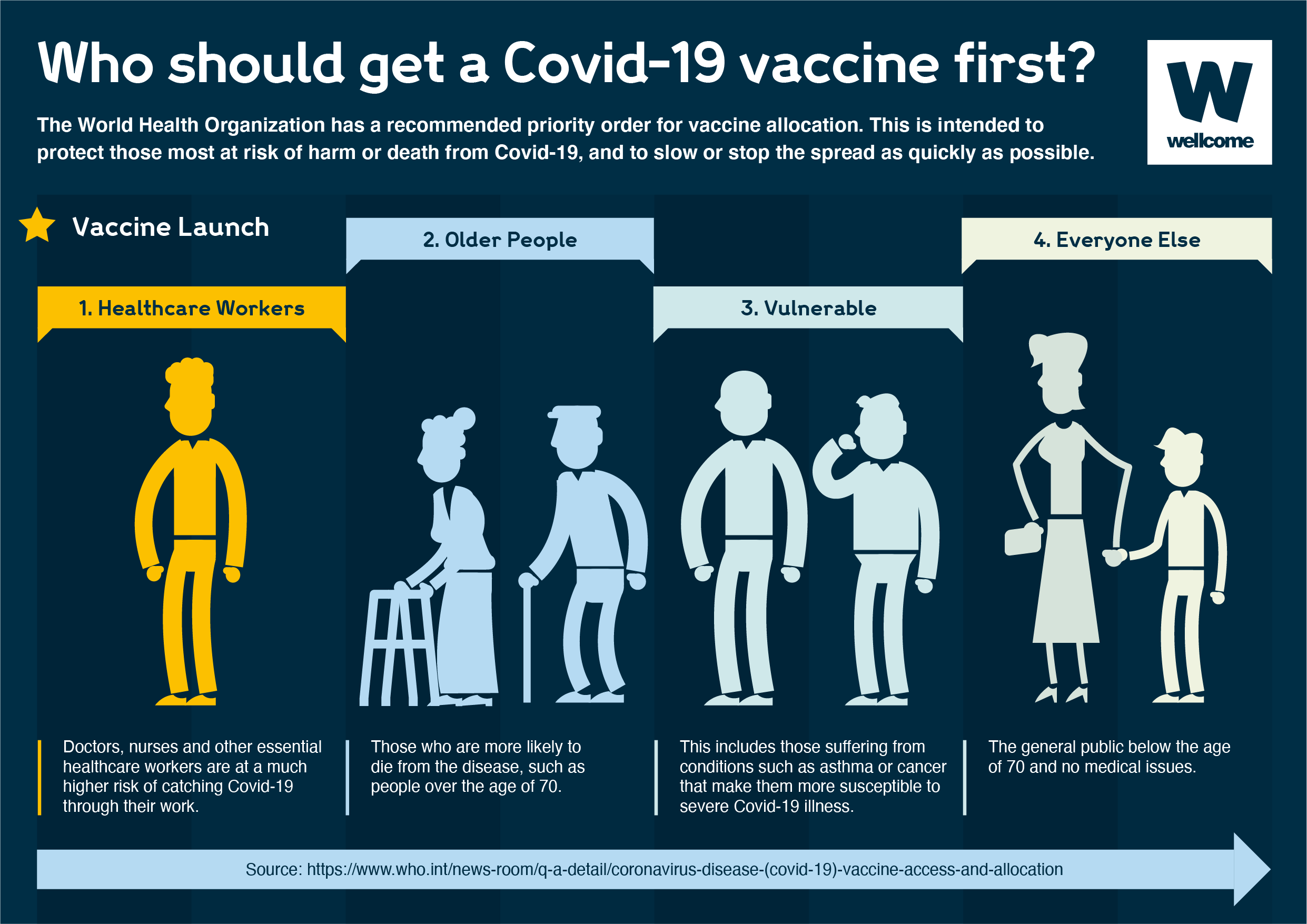

The World Health Organization have a recommended priority order starting with healthcare workers, the oldest (who are most at risk of serious illness and death) and those who are vulnerable due to other health conditions. Most countries are basing their response on this. We may also need to review recommendations taking into account new virus variants and outbreaks that occur due to them.

However, prioritisation should be done with the global situation in mind, as well as the domestic. Governments naturally consider their own populations when making decisions on vaccine roll out, but with a disease such as Covid-19 that does not respect borders this can lead to problems like those we are seeing currently with global vaccine access.

Who should get a Covid-19 vaccination first? The World Health Organization has recommended a priority order for vaccine allocation.

It’s vital that we think globally as well as nationally when distributing the vaccines. Without worldwide measures, Covid-19 will remain active, kill thousands or even millions more, develop into new dangerous variants, and continue to spread.

A virus often mutates and creates new strains as it spreads. We have seen this play out in recent months, with highly transmissible new alpha, beta and delta strains responsible for devasting new waves around the world. Although mutations will always occur, by limiting the presence of the virus worldwide we can reduce both the spread of current strains and the risk of new strains forming that could further threaten the global population. Any new variant that develops could potentially escape protection provided by the vaccines, undermining the monumental efforts made globally to vaccinate the world.

We need to prioritise global access to vaccines and ensure they reach the most vulnerable people, everywhere. Further, the vast majority of people in low-income countries – including healthcare workers – have not received their first dose of a vaccine. We are quickly moving towards a dual pandemic where high-income countries have access to multiple vaccines and high levels of vaccination across their populations while poorer countries are locked out of access to vaccines. Sharing doses with COVAX is the fastest way to prevent this from happening. Countries with high levels of vaccination and access to high numbers of doses, such as G7 and EU countries need to step up and share doses faster.

COVAX is a global initiative that has been designed to help create global vaccine access. Around half of the world’s population live in countries reliant on COVAX for access to Covid-19 vaccines. COVAX was aiming to deliver 1.9 billion doses by the end of 2021, but so far has only been able to deliver around 10% of that. This is due to shortages in supply and over purchasing by wealthy countries making deals directly with pharmaceutical companies.

Economic recovery is predicted to take much longer if we don’t distribute the vaccines around the world because we cannot have a healthy global economy if there is still a risk of Covid-19 spreading. By using the vaccines fairly, it’s estimated we could see economic benefits of up to $466 billion in the next five years.

Audio: Sir Jeremy Farrar and Anna Mouser (Vaccines Policy Lead, Wellcome) discuss how important global vaccination is in bringing the Covid-19 pandemic under control.

Some high-income countries are purchasing additional vaccine doses for booster campaigns, despite there not being evidence for the broad use of boosters.

If wealthy countries begin to negotiate additional deals for booster shots, we risk further widening the gulf between richer and poorer countries, with more people being infected and becoming seriously ill in poorer countries. This in turn increases the risk of dangerous variants developing as the virus spreads in unvaccinated populations and prolonging the global pandemic.

It is likely that if wealthy countries pursue purchasing booster shots it will impact the supply that is available for COVAX and the countries reliant on them.

A booster shot is a dose of vaccine given after someone has completed the original full course of vaccination. They may be required for two reasons, firstly due to the emergence of a new variant that current vaccines are not protective against or to ‘boost’ their protective immune response and maintain protection.

Boosters are almost always the same as the original vaccine, but they can be different. For Covid-19 there is one ongoing study as to the effectiveness of mixing and matching different vaccines such as AstraZeneca and Pfizer. Pharmaceutical companies may also tweak and update the formula of Covid-19 vaccines in response to the variants that have developed over the past year.

Boosters are common for other vaccines such as MMR and tetanus and are given at different intervals for different vaccines. The decision to introduce boosters for all vaccines is based on on-going surveillance and vaccine effectiveness monitoring.

Should we be administering Covid-19 booster shots to people later this year?

It is still unclear whether boosters will be needed but the question is under consideration by researchers. The World Health Organization (WHO) currently does not recommend boosters and has gone further to say that there should be a moratorium on boosters until the end of September 2021 and we have been able to vaccinate at least 10% of the population in every country globally. Despite this, many countries are already planning for booster campaigns starting in September. The WHO moratorium does not preclude giving doses to specific populations who might not get protection from the standard vaccine regime, such as those who are immunocompromised.

Since clinical trials on these vaccines only began a year ago, and roll out across populations is still underway, there is limited data on how long the protection from current doses lasts and whether an additional booster dose would be beneficial and for whom. However, evidence to date suggests that there is extremely high and long-lasting effectiveness against serious illness from mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna) vaccines. We need data to guide the use of boosters and therefore it is currently too early to decide whether they are necessary or not.

Before countries rush to secure boosters, we must improve global access to Covid-19 vaccines. The biggest risk we currently face is not the decline in vaccine effectiveness but the millions of people currently without access to a vaccine. It is essential that the global community prioritises the most vulnerable people and healthcare workers who are still without protection in many countries.

Can countries share vaccines and provide boosters to their own populations?

Vaccine dose sharing and providing boosters do not have to be mutually exclusive. Analysis carried out by the Gates Foundation ahead of the G7 in June 2021 showed that even if the G7 and EU countries vaccinated everyone 12 years of age and over and provided boosters (with 80% uptake), they still could share more than 1 billion vaccine doses this year. This analysis also takes into consideration up to 10% wastage. Analysis has also shown that the UK will have access to 210 million more vaccine doses than it needs in 2021, even if it were to vaccinate all over 16s and offer boosters to the most vulnerable this autumn.

Many countries have made big commitments to share vaccine doses over the next year, but we need countries to share vaccines now. COVAX has not been able to deliver as many vaccines as forecast and with cases and deaths rising in many parts of the world, time is of the essence. The pandemic is spreading rather than winding down in many countries, it took ~1 year for global cases to reach 100 million – and just 6 months for global cases to hit 200 million. Deaths across the African continent from Covid-19 have surged 80% in the past four weeks. We need the G7 to act urgently to meet their commitments while there is still a limited vaccine supply.

How should the global community prioritise the distribution of Covid-19 vaccines to give us the best chance of ending the pandemic and saving lives? Could booster vaccines impact global roll out?