How the response to Ebola outbreaks shows why we need to prioritise preparedness

Ebola is now a disease that can be diagnosed and treated. To prevent Ebola outbreaks from occurring in the first place, the world needs to be proactive to be better prepared. It can do this by prioritising community engagement, vaccination, filling research gaps and investing in infrastructure in high-risk countries.

Health workers move a patient to a hospital after he was cleared of having Ebola inside a MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) on 4 November 2018 in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In 1976, a new virus was discovered in what is now called the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The disease, which killed many of those infected, was named after the nearby Ebola river.

Ebola is a zoonotic disease, meaning that it started in an animal host before spreading to humans. It is transmitted through direct contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated clothing and other personal items of symptomatic or deceased patients or animals.

Without treatment, the average case fatality rate of Ebola is around 50%.

A vaccine candidate was developed in 2005, but a failure to prioritise epidemic preparedness and research meant that important safety trials, which can be done at any time, were not completed until the largest epidemic began nine years later.

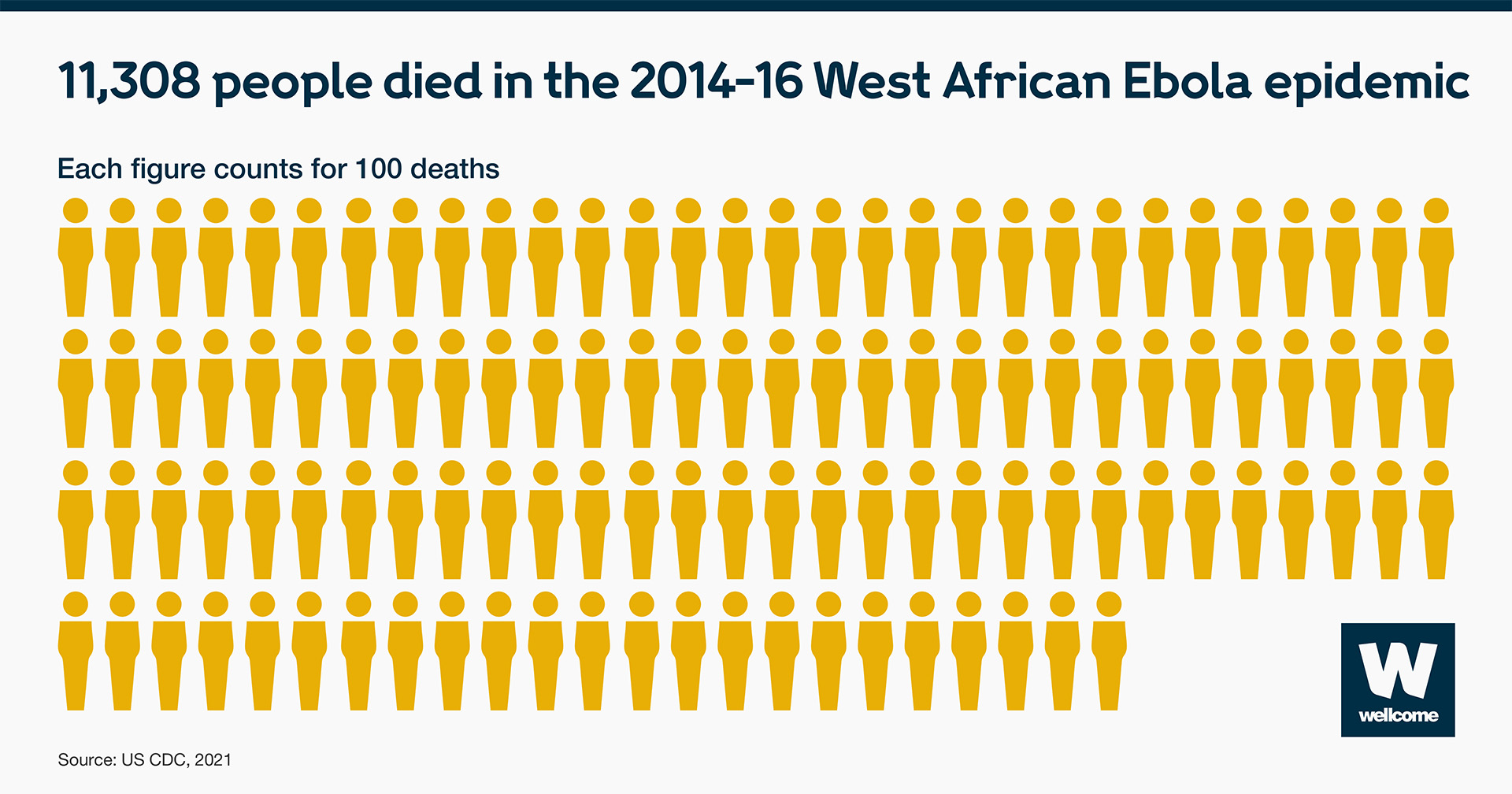

Source: CDC, 2021

The West African Ebola epidemic of 2014 resulted in more than 28,000 suspected cases and 11,000 deaths. At the time, there were no vaccines and no treatments to help combat the disease. Because the amount of virus present in the body is known to be highest at point of death, traditional funeral practices – which include washing and touching the corpse – led to many people becoming infected in the earlier stages of the epidemic.

This epidemic was the catalyst for prioritising critical research to have better tools to prevent and respond to Ebola.

First, aid workers and researchers worked with the communities that adhered to traditional burial practices to negotiate slightly different practices. This made sure that future burials and funerals were medically safe but still acceptable to the community. Burial teams made up of local volunteers, gained the trust of the communities, which was critical to success.

Second, research took place on the frontline to help contain outbreaks. In response to the outbreak, public health officials and the pharmaceutical company Merck fast-tracked rVSV-ZEBOV, a single dose experimental Ebola vaccine. After a highly successful field trial in 2015, and further used to contain outbreaks in DRC in 2018, the US and EU regulators approved the vaccine in 2019. A second two-dose vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson was given the green light in Europe in 2020.

However, while enhanced community awareness of how to tackle Ebola, vaccines and improved surveillance has proved successful at ending the spread of infection, new outbreaks continue to occur.

In 2021 Ebola outbreaks were declared in the DRC and Guinea. Genetic sequencing of samples from the DRC outbreak suggests that cases were linked to cases in the area during the 2018-2020 outbreak. Similarly, sequencing of samples from the Guinea outbreak were compared to sequences from cases during the 2014-2016 West Africa outbreak. This research suggests that both 2021 outbreaks were linked to the persistent infection of a survivor – highlighting the need to conduct prevention-led vaccination campaigns.

It’s unlikely that we would ever be able to prevent Ebola from reappearing completely because of the animal reservoir, but we can do more to protect those at risk.

1. Community engagement and education

Community engagement and social mobilisation are central to effective preparedness. Response teams must work with the community, religious leaders, journalists, radio stations, and partner organisations to build awareness of Ebola and community confidence in the tools that combat an outbreak.

2. Widespread surveillance and monitoring systems

Reinforcing disease surveillance across high-risk countries will help prevent any chance of a surprise resurgence. This requires a combination of a well-trained healthcare workforce with knowledge of the symptoms to identify, and the laboratory facilities to confirm the presence of the virus.

3. Prevention-led vaccination strategies

Immediate response to outbreaks is critical to their containment. Proactive vaccination strategies in high-risk areas for Ebola could help curb the spread, and support the ‘ring vaccination’ approach– vaccinating healthcare workers and those in close contact with Ebola cases – to stop the virus from spreading.

4. Prioritising filling the research gaps

Critical research is required to help better prevent and respond to Ebola outbreaks in the future. These gaps have been highlighted through a global consultation with researchers, public health institutes, and at-risk countries and outlined in the draft World Health Organization R&D Roadmap for Ebola and Marburg.

It should be noted that current Ebola vaccines have been developed to target and protect against one type of Ebola virus. But we know that there are other Ebolavirus species that cause outbreaks and we need to invest in research to develop new Ebola vaccines to target these species. We need to invest in research to develop new generations of Ebola vaccines to target any new variants that emerge.

All of these strategies require funding. From the provision of millions of vaccine doses, to the infrastructure and training to deliver them. But without global investment in these areas, we will continue to see outbreaks.

And Ebola is also far from the only deadly virus that humans face. In 2018, measles killed more than 140,000 worldwide, and influenza is estimated to result in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths according to the World Health Organization.

We must invest in prevention and strengthen health systems, not just reactive responses, to stop an infectious disease outbreak turning into a deadly epidemic.

Ebola is now a disease that can be diagnosed and treated. To prevent Ebola outbreaks from occurring in the first place, the world needs to be proactive to be better prepared. It can do this by prioritising community engagement, vaccination, filling research gaps and investing in infrastructure in high-risk countries.