From epidemics to eradication: how the world is ending polio

Polio, one of the most feared diseases of the 20th century, is close to eradication after a 30-year global vaccination campaign. We look at how good science, vaccine equity and long-term investment is helping to end the disease.

A health worker administers polio vaccine drops to a child during a polio vaccination campaign at a slum area in Lahore on September 20, 2021.

Polio (poliomyelitis) is an infectious disease caused by a virus. The disease mainly affects children under five years of age and symptoms usually last up to ten days. One in 200 polio infections lead to permanent paralysis, and if a person’s breathing muscles are affected, it can be fatal.

It is spread from person to person through contact with the faeces of someone infected and less commonly through ingesting contaminated food or water, or through droplets from a sneeze or cough.

Types of polio

- Wild poliovirus: There are three serotypes of wild poliovirus. Serotypes are groups within a species of microorganisms, such as bacteria or viruses, which share a similar characteristic. They are closely related but immunisation to one serotype does not create immunity to another, so existing polio vaccines target all three strains. Type 1 is historically the most prevalent worldwide and continues to cause infection today. Type 2 was declared eradicated in September 2015 and type 3 was eradicated in October 2019.

-

Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus: A weakened form of the virus used in the oral polio vaccine (OPV) can sometimes transform into a disease-causing strain. This occurs rarely and in highly under-immunised populations.

Many diseases can spread between animals and humans. So, even if an entire population is vaccinated, the disease could still be circulating among animal species.

Polio, however, has never been documented in animals, which makes eradication possible. If the virus can’t find a vulnerable human body to spread to, it loses its infectiousness.

Achieving eradication requires the development of vaccines, mass vaccination campaigns, successful global cooperation and continued surveillance.

While polio has existed for thousands of years, it was not perceived as a major public health threat until the early 20th century when it changed from an endemic disease to an epidemic disease across the USA and Europe.

The cause of this transformation was the improved sanitation of industrialised countries. People were less exposed to the virus at a very young age and less likely to develop immunity. This made them more susceptible to polio and more likely to develop severe symptoms. Faced with an ancient, infectious and incurable disease, scientists around the world focused their efforts on better understanding and developing a vaccine to prevent it.

Some significant breakthroughs in the first half of the 20th century included discovering the poliovirus itself (1908), recognising the existence of antibodies in the blood specific to the virus (1910), identifying its different serotypes (1931) and showing how the virus could replicate in tissue culture (1948).

IPV vaccine

The first polio vaccine, known as the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), developed by American physician and medical researcher Jonas Salk, was approved in 1955. It is delivered by injection and protects against paralysis but does not stop transmission of the virus to others.

At the time, around 60,000 children in the USA alone were being infected annually. The virus was most pervasive in children aged five to nine years and around one-third of reported cases were in people aged over 15. But while children were in line to get vaccinated, many American teenagers who were also at risk were not.

In an attempt to boost the nation’s vaccination rate, singer Elvis Presley was recruited to help the public health campaign. The world-renowned star agreed to be vaccinated in front of the press. In the six months that followed, polio vaccination rates among American teenagers increased to 80%.

UNITED STATES - OCTOBER 28: Elvis Presley receiving a polio vaccination from Dr Leona Baumgartner and Dr Harold Fuerst at CBS studio 50 in New York City.

Another gamechanger was the formation of Teens Against Polio, a group set up by teenagers with the help of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. Teens Against Polio campaigned door-to-door across the nation and organised social events where the price of admission was a jab in the arm. Its advocacy helped transform attitudes to the vaccine. The annual occurrence of polio in the USA decreased by almost 90% between 1950 and 1960.

OPV vaccine

A second vaccine, known as the oral polio vaccine (OPV), was developed by American physician and microbiologist Albert Sabin and approved in 1961. It quickly became the predominant vaccine used around the world.

The OPV is easier to administer – given with just two drops into the mouth – and cheaper to produce. It is made with live weakened polioviruses that can replicate effectively in the gut and build a child’s immune response. It can also provide ‘passive’ immunisation to others around the vaccinated child when excreted.

However, OPV can cause another form of polio in some rare episodes and in communities with low immunisation rates, called circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs). This occurs when a vaccine virus spreads from one child to another over a longer period of around 12 to 18 months. In these instances, the virus may mutate and cause paralysis like the natural form of poliovirus does.

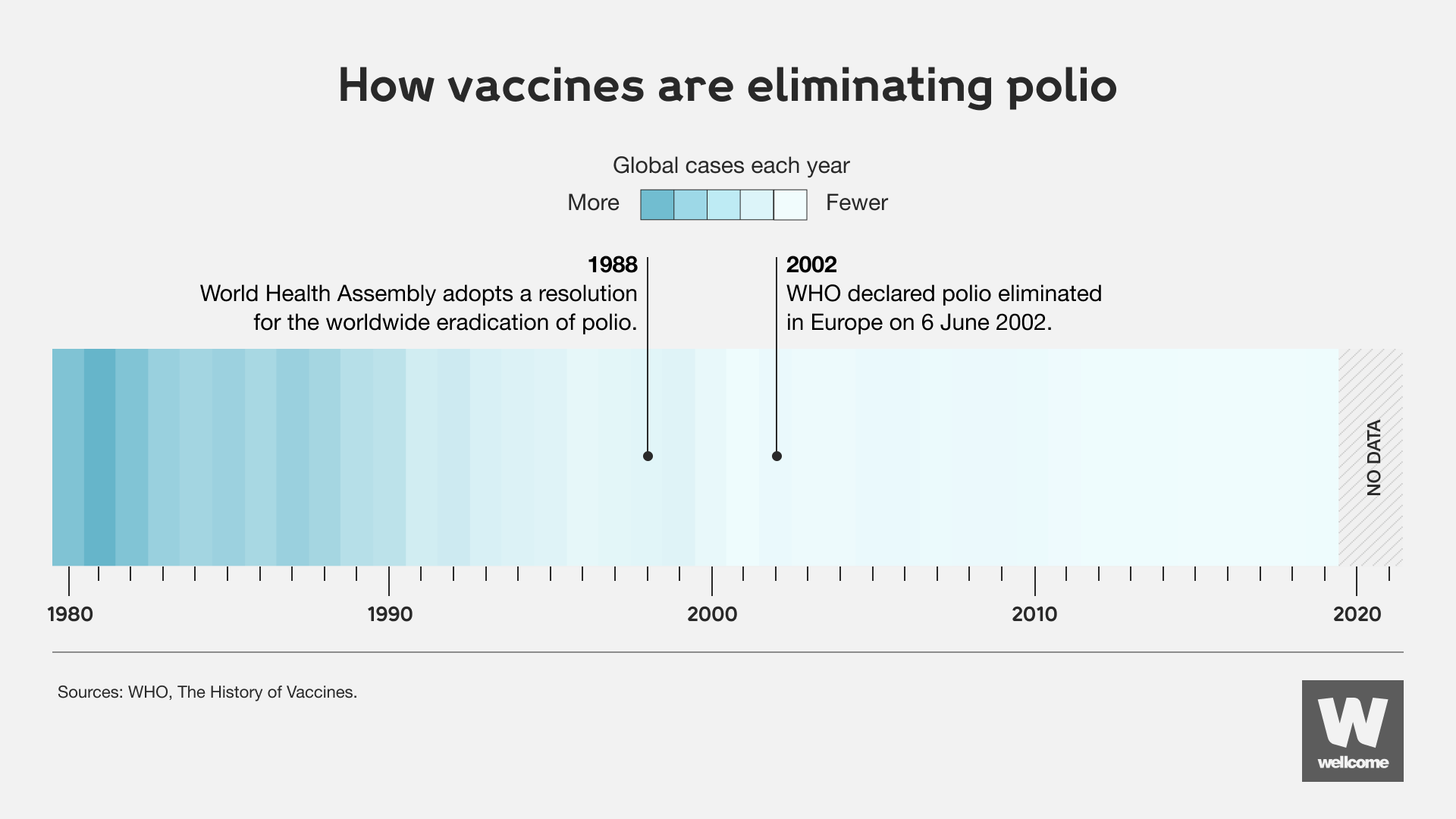

By 1988, the two vaccines helped stop the spread of polio in the USA, UK, Australia and much of Europe, but the disease was still endemic in 125 countries.

Without an equitable global vaccination programme, polio prevailed in most parts of the world. Getting vaccines, tests and treatments where they’re needed the most during epidemics is critical to driving down infection rates and saving lives.

That’s why, in the same year, the World Health Assembly – the governing body of the World Health Organization (WHO) – launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) to end all wild and vaccine-derived poliovirus.

The GPEI was spearheaded by national governments, WHO, UNICEF, Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and later joined by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

How is the GPEI eradicating polio?

1. Routine immunisation

To increase population immunity, the GPEI aims to give children in developing and endemic countries at least three doses of OPV in their first year of life. Countries free of polio must also continue a routine immunisation with OPV or IPV to prevent the re-emergence of the virus through travel from other countries.

2. Mass immunisation campaigns

Supplementary immunisation complements routine immunisation by increasing vaccination coverage. Every child under five years of age receives two doses of OPV, regardless of previous immunisation. This helps to reach children who have no or partial immunity and provides further protection to those who have immunity.

3. Surveillance

Active polio surveillance helps detect any new cases and determine their origin. This is done through reporting of illness and laboratory testing stool samples from children under 15 who develop acute flaccid paralysis. Environmental surveillance, such as testing sewage, can also confirm the presence of polio in communities.

4. Targeted ‘mop-up’ campaigns

In communities where polio is known or suspected of circulating, ‘mop-up’ campaigns are carried out. These are door-to-door immunisations in priority areas where polio cases have occurred in the last three years and where there is poor access to healthcare.

Source: WHO, The History of Vaccines

The fight against polio relies on global collaboration, innovation and funding.

Three decades since the GPEI was launched:

- The number of cases worldwide of wild poliovirus has fallen by 99.9% – from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to five confirmed cases in 2021.

- The WHO’s Region of the Americas, Western Pacific Region, European Region, South-East Asia Region and Africa Region have all been certified free of wild poliovirus.

- An estimated 18 million people have been saved from paralysis and 1.5 million childhood deaths have been prevented.

- Wild poliovirus is now only found in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Both countries have implemented national emergency plans to increase accountability, improve vaccination campaigns and reach more children.

- A new vaccine to address the risk of cVDPV is being rolled out.

The campaign has made huge progress, but polio remains a global public health priority.

The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 affected the GPEI’s work significantly.

Polio campaigns were paused in 28 countries and 23 million children missed out on receiving basic vaccines, creating an immunity gap and causing a surge in cases. More than 1,200 children were paralysed by wild and vaccine-derived poliovirus in 2020, more than double the number in 2019.

However, an intensified effort in 2021 to reach millions of children in Afghanistan and Pakistan helped achieve the lowest polio transmission in both countries to date. Building on this turning point, the GPEI launched a new strategy for 2022 outlining a four-year plan to eradicate polio.

As of 2022, wild poliovirus remains endemic to Pakistan and Afghanistan. Additionally, this year several countries that were declared free of polio have reported cases of vaccine-derived poliovirus.

In July, the US reported its first case of paralytic polio in New York since the 1990s and found evidence of the virus in the state’s wastewater. As polio vaccination rates are low in the area, officials declared a state of emergency. Poliovirus has also been detected in wastewater in the UK and Israel.

The emergence shows the risk of low vaccination rates in any population. When children receive the OPV vaccine, they shed the vaccine virus in their stools for short period. That’s why vaccine-derived polioviruses are sometimes detected in wastewater. If a population then has low immunisation rates and these vaccine viruses can circulate, they can eventually mutate and take on a form that can cause paralysis. This mutated poliovirus can spread and lead to other circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses.

Recent polio cases are evidence that diseases do not respect borders and if polio exists anywhere in the world, unvaccinated children everywhere are at risk. Failing to eradicate poliovirus completely could result in a resurgence of the disease – and 200,000 new cases could appear annually within a decade. In October 2022, world leaders committed billions to fund the GPEI’s new strategy, and more than 3,000 international scientists and health experts signed a declaration to endorse the plan. We must continue to improve vaccine demand and access, increase global investment and coordination and immunise every child until transmission stops.

This article was first published on 16 February 2022.