Albert's story: a search for the ideal research environment

As a computational chemist, Albert Antolin is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow at The Institute for Cancer Research, London, in the Department of Data Science. He’s leading a multi-institutional project, working with companies in artificial intelligence and pharmaceuticals, to expand the use of cancer drugs in selected patient populations.

For many scientists, finding the right research area takes time. Not for Albert Antolin. He knew early on that he wanted to discover new drugs. But to find the right research environment he had to move from industry to academia, and to a new country.

Albert learned to deal with setbacks early on in his career.

He’d joined a pharmaceutical company in his hometown of Barcelona immediately after finishing his Master’s. He felt that industry would offer the best environment for his goal: to discover new drugs to help cure diseases.

Everything went well at first. "I had the best time of my life there, because doing drug discovery is really rewarding. It was a very small company, but the perfect size to learn everything. And it was a very multidisciplinary environment, so my perspective was really wide."

Albert wanted to do his doctoral studies at the company but it decided to close its research arm, and he was forced to abandon his plans. "That was a very sad moment in my life."

He began a PhD in academia, at the Pompeu Febra University, but found the change in culture unsettling. "It was a very different way of working," he says. "I had moved from working in a team of scientists who needed my input to continue developing a drug, and where my work was having a real impact, to traditional academic research, which is more about you and your project."

His first year back in academia was hard. "I wasn’t completely sure that the project I had been given by my supervisor was the right one. We tried some side projects, to do drug discovery in an academic setting, and it didn’t work out."

Ramon Llull University, Barcelona, Spain

SALVAT Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain

Ramon Llull University, Barcelona, Spain

Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain

The Institute of Cancer Research, London

The Institute of Cancer Research, London

Eventually, within the topic he was given, Albert found a research question that excited him.

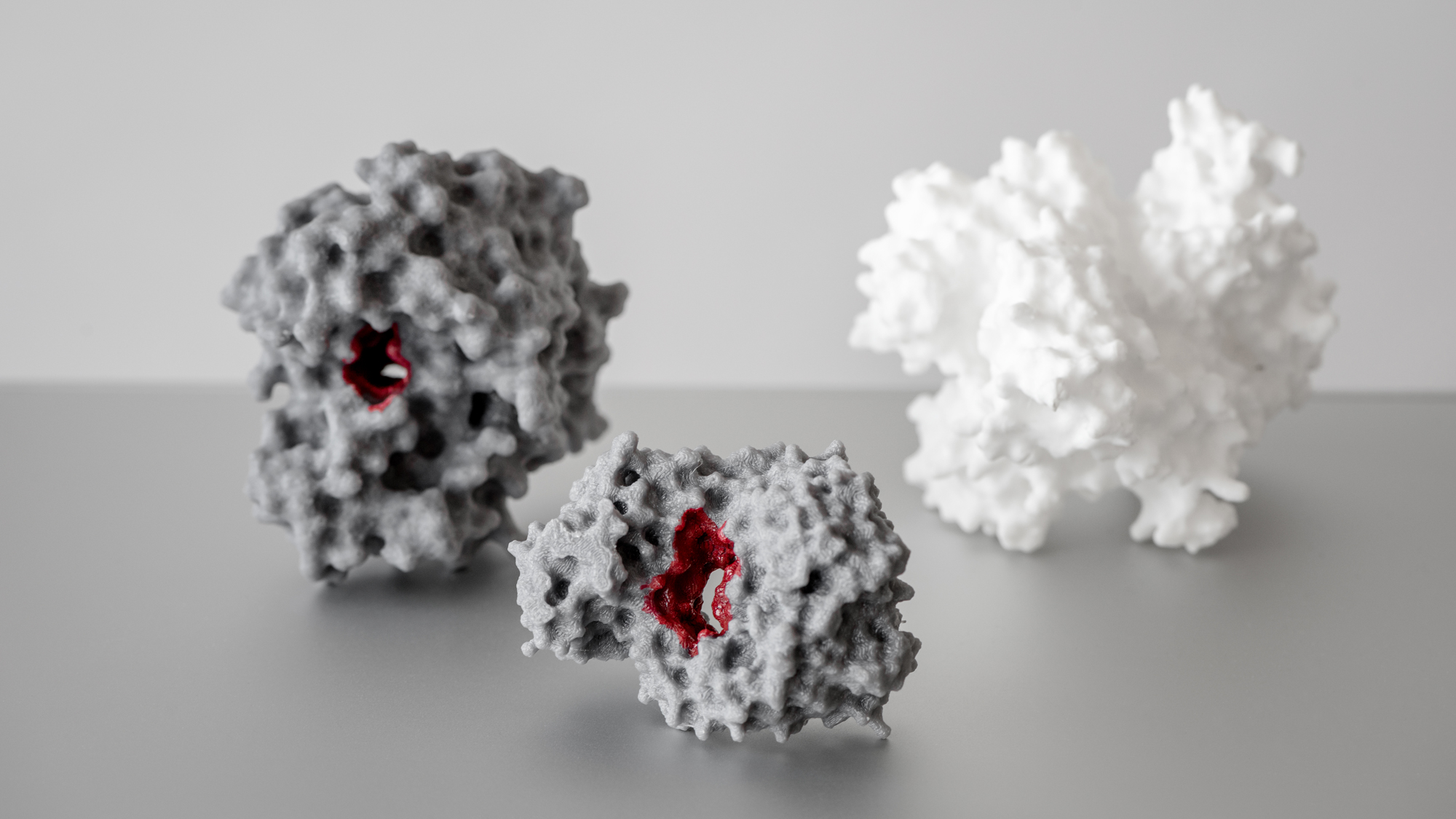

His lab at the university was developing computational methods to predict when a drug might interact with an unintended target, to help explain its side-effects or find different ways of using it.

"But we had never applied these methods to chemical biology," he says. So, instead of looking at drugs, Albert used computational methods to look at small molecules that were being used as chemical tools in biomedical research.

"Researchers use these chemical tools thinking they are completely specific for a given protein, and often they’re not. We were among the first to flag this."

Although he was happy with his research, Albert was still missing the impact he wanted his work to have in drug discovery or through clinical application. He began to look at his options for returning to the pharmaceutical industry once he’d finished his PhD.

Then he discovered The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London.

"It’s a really unique place. The cancer therapeutics division has the potential of a small biotech company. They’ve found a way to do drug discovery and academic research. And that’s incredibly attractive because they’re not subject to the pressures that a big pharma company is."

But also, the ICR is supported by organisations like Cancer Research UK and Wellcome. "Without this specific way of funding it’s very difficult to do drug discovery in an academic setting."

Albert felt strongly that the ICR was the right place for him to carry on his research career. But there were several hurdles to overcome.

"I really wanted to move there," Albert says, "but of course it’s never easy to move country. And it wasn’t someone at the ICR saying to me that I had a postdoc position, it was me saying that I wanted one, so I had to find a fellowship."

After pitching his research idea to the ICR, Albert applied for a Marie Curie Fellowship and got funding for a two-year project. He was so sure that the ICR was the right institution for him that he turned down a role he’d been offered at a big pharmaceutical company.

"Moving to London was great, but very challenging," he recalls. Albert was recently married and his husband, a medical doctor from Colombia, found it more difficult to relocate.

"I was the driver behind the move. My husband wanted to move too, but probably wouldn’t have chosen London. It’s really hard when you’re trying to juggle two careers."

Fortunately, the ICR lived up to his expectations.

First, there were his supervisors.

"You gamble a lot with these moves. There are a lot of postdocs who move to labs where they know their supervisor so the transition is easy. I didn’t. It looked great on paper, but personal relationships are very important to me and I didn’t know how they’d work out. Supervisors play a big role in the environment they create in their labs. And my two mentors have been amazing at this.

"If you want to become a good sculptor, you often try to learn from someone who’s very good at their craft. In science it’s similar. Good mentors support their peers and show them how to do science well. It’s not a mathematical thing – telling you ‘do this, this, and that’. Every person has a different path and story, and we learn from successful people."

Second, the research environment was even more inspiring than he’d hoped.

Albert believes that great discoveries happen when you start moving out of your comfort zone and begin exploring other disciplines. And at the ICR he was surrounded by medical doctors – from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust – who were seeing hospital patients and doing research, which doesn’t happen in industry.

"I’m the only chemist in my lab and I’ve never worked with clinical data before so it’s a challenge. But it’s also how you discover new things."

Conversations with his medical colleagues sparked new research ideas.

"Some patients have an exceptional response to a certain drug, and we often don’t know why. Often these drugs don’t work for the general population, so they don’t get approved. These are missed opportunities because if we could understand why these drugs work for these very few patients, we could perhaps find other patients who would also respond to them."

Although Albert had plenty of ideas, he still needed to get funding to explore them.

As his Marie Curie fellowship was finishing, Albert started to look for other grants to further his research at the ICR. He found the Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellowship.

"It was asking applicants to be very ambitious – imagination was the only limitation."

What most excited Albert about the fellowship was the possibility of setting up a multi-institutional project to bridge the gap between academia and industry. He brought in a pharmaceutical company and an artificial intelligence company to work on his project.

"The great thing about the conglomerate I built around my Wellcome fellowship is the possibility to have an impact on patients’ lives," he says. "We are side by side with The Royal Marsden. I see patients at the canteen when I go to the hospital, so I have a very real sense that I’m not studying something purely academic. If we could make a very small contribution, it would be very rewarding."

Albert is in the second year of his fellowship and enjoying the freedom to pursue his own ideas.

"It’s not common to have this opportunity. Of course it’s a huge responsibility, and there are always challenges and things that you didn’t plan for, but you have to find ways of solving these problems by yourself."

In terms of his career, he’s now at a stage where he can plan for the future. "Because it’s four years, the Wellcome fellowship gives you a lot of peace of mind and support. I have a clear idea of what I want to achieve now, and what the next steps are."

Like most researchers at this career stage, Albert is well aware of the obstacles he’s likely to face.

"There is a lot of pressure on young researchers about how much you need to publish to go on to the next stage. I’m glad that Wellcome is saying explicitly that they will evaluate you on your research, not on if you’ve published in Nature or Science."

Albert says resilience is essential in a science career.

"You have to develop a very thick skin. If we knew that research was going to work, it wouldn’t be research. So many times it doesn’t work, many research applications don’t get funded, and papers get rejected."

He adds: "The scientific career is very competitive. If you want to continue after your PhD, you need to be aware that it’s a challenging path and it’s not for everybody. You have to really value your independence, really value following your own ideas, be prepared to juggle your personal life – in my case moving country – and to be resilient to a lot of rejection and frustration."

He’s convinced it’s all worth it. "You can really contribute to the world. There are fascinating questions out there that we don’t yet know the answers to. And if you work in a disease-related discipline, there are patients out there who could benefit from your work. It’s intellectually stimulating, but also the impact you can have is huge. It’s a privilege."

Albert always knew the type of research he wanted to do. But to find the right research environment he had to move from industry to academia, and to a new country.