Exercise has been shown to improve depression, but we don’t know how it works exactly. We spoke to Professor Jonathan Roiser about his new research study that could help fill in the gaps – and bring us closer to better treatments.

Professor Jonathan Roiser has been awarded funding to research the antidepressant effects of exercise.

From quick boosts in mood to alleviating long-term depression, many studies have shown the powerful impact of exercise on mental health. For some people, the antidepressant effects of exercise can be just as effective as conventional treatments like therapy or medication.

But “exercise is very rarely prescribed,” says Jonathan Roiser, a Professor of Neuroscience and Mental Health at University College London.

That’s one thing he hopes his new research project will help to change.

Professor Roiser’s project – funded by a Wellcome Mental Health Award – will investigate how physical exercise exerts its antidepressant effects.

To do that, Roiser and his research team will run one of the largest trials of its kind on depression and physical activity. Over eight weeks, they will assess changes in brain systems that process reward and effort in 250 participants with depression to better understand how exercise delivered by coaches can alleviate symptoms.

Their hypothesis is that physical activity can treat depression by changing motivational processes in the brain in ways that existing mental health interventions fail to address.

And the results could help transform treatments for people with depression.

We want to use a ‘back translation’ approach to investigate what makes interventions for anxiety, depression and psychosis effective. That means taking an existing effective intervention or approach and testing hypotheses using experimental methods to understand what makes it work.

Our funding award is providing up to £5 million to 12 research teams to do just that.

The goal is to inform the improvement of existing treatments and the development of new ones.

Research has shown different types of physical activity can improve mental health, including aerobic exercises like running and swimming and anaerobic exercises like weightlifting and high-intensity interval training.

However, Roiser’s research will focus on aerobic exercises, which have shown the strongest antidepressant effects.

Participants aged 18 to 65 will attend hour-long group gym sessions three times a week tailored to their fitness levels and led by trained instructors. One group will take part in aerobic exercises, while a second control group will practice stretching and relaxation techniques.

The result, according to Roiser, will help uncover new insights into the mechanisms at work. “Through this careful, controlled experiment, we should be able to draw much stronger conclusions than many previous studies that have tried to do this,” he says.

The research study will focus on aerobic exercises – like running on a treadmill – which have shown the strongest antidepressant effects.

Professor Jonathan Roiser and his colleague Emily Hird, a Senior Research Associate at UCL who will help run the study.

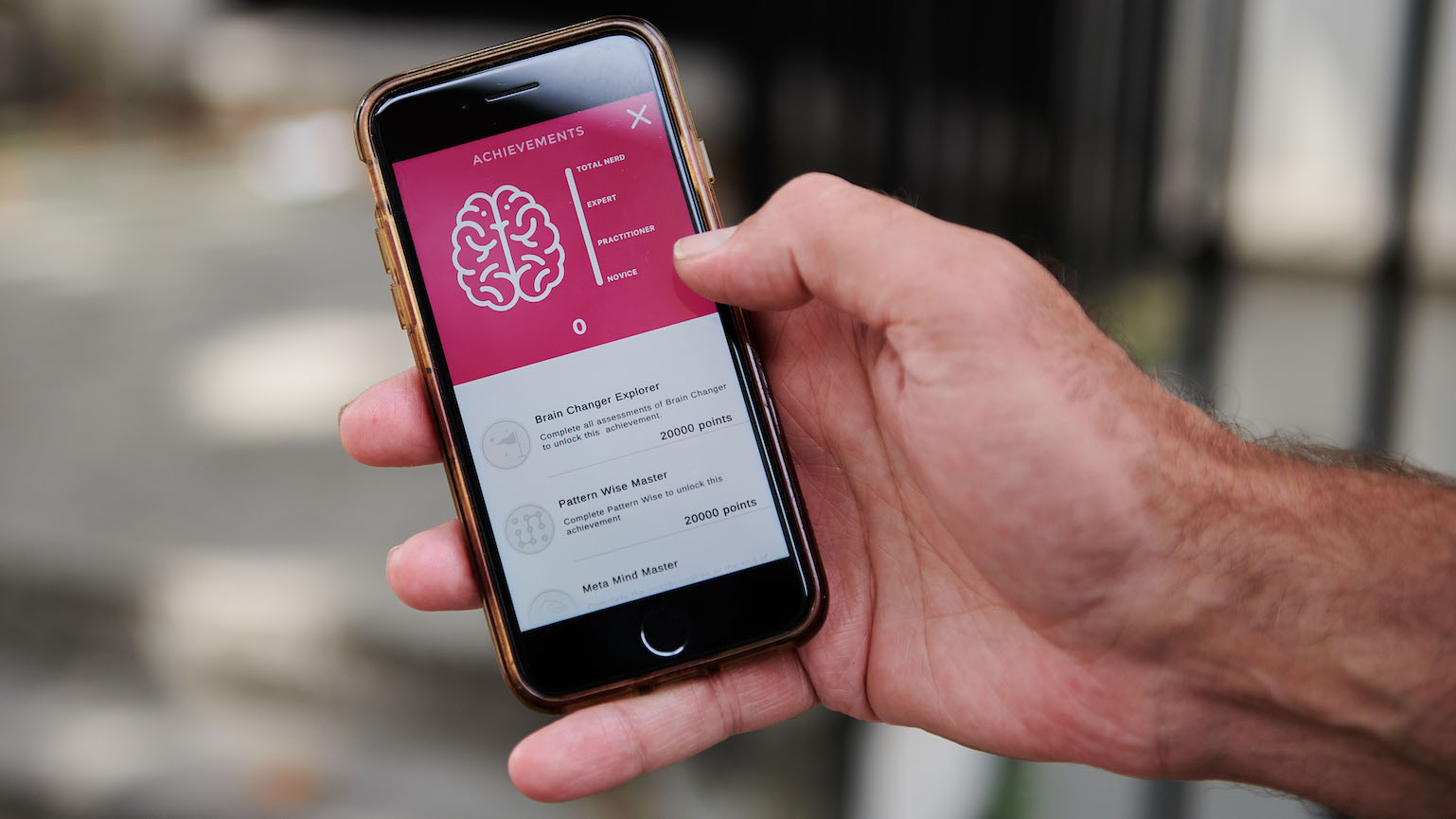

Participants in the study will rate their depression symptoms using an app called Neureka.

The team will measure each participant’s general depressive symptoms and anhedonia symptoms – the loss of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding activities – before, during and after the trial using weekly questionnaires.

“When people get motivated by things, they often have to make a decision and put in effort to achieve their goal. Think about cooking a new dish: you have to decide what to cook, find a recipe and figure out the ingredients. Then comes the physical effort of going to the shop, preparing and cooking the meal. For someone with depression, even thinking about these steps can be overwhelming. The amount of effort involved seems too high, and they may give up. We’re interested in the cognitive processes involved in these instances,” says Roiser.

But the research will also extend beyond psychological processes, with the team using brain scans, blood samples to measure immune and metabolic changes and a technique called positron emission tomography to measure changes in dopamine levels – a core part of the brain’s reward system.

“It’s not a study that any one person can run by themselves – it really is a team effort,” says Roiser.

His team of experts will help gather insights from people with lived experience of depression to co-design the study, help run the trial, plan the exercise intervention and measure the effects in participants. “When you’re doing this work, it has to be interdisciplinary, because nobody can possibly be an expert in all of these areas,” he says.

The world is struggling with a mental health crisis, with around 280 million people living with depression. While treatments for depression exist, we don’t know enough about how they work.

Understanding how exercise helps depression could provide a new solution, help improve existing treatments and inform the development of new ones.

Ultimately, Roiser hopes this research will show doctors that exercise is a valuable prescription that is free and accessible, and that does more than help the mind.

“There are also good knock-on effects from physical activity, not just in terms of mental health but also on physical health.”

But what excites Roiser the most about the research is its potential to understand who may benefit the most from exercise.

“We have these descriptive labels in mental health research, like depression, anxiety and psychosis, but they’re umbrella terms that likely incorporate lots of different types of conditions,” he explains.

“There’s a tendency to lump everyone with a diagnosis like depression together and think that all of the mechanisms are the same in all individuals, and so we’ve ended up with treatments that don’t work for everyone.”

Instead, he says, “it’s quite likely that physical activity will be really helpful for some people and not so helpful for others.”

Through this study, Roiser and his team hope to learn about which people get the most help from exercise as a treatment, and whether this can be explained by changes in particular brain processes. This knowledge could be a step towards finding better ways to intervene, manage and resolve mental health conditions.

“That’s my real hope,” says Roiser, “that eventually, we’ll be able to target treatments more strategically and personalise them at a much earlier stage – which could make a big difference in clinical practice.”

We’re funding research to help create transformative change in early intervention for anxiety, depression and psychosis. Explore our current funding call:

Mental Health Award: Accelerating scalable digital mental health interventions

Exercise has been shown to improve depression, but we don’t know how it works exactly. We spoke to Professor Jonathan Roiser about his new research study that could help fill in the gaps – and bring us closer to better treatments.