In South Africa, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) kills thousands of people every year. These Wellcome-funded research teams are working with local communities to better understand the impacts of AMR – and to develop interventions that work for the people who need them.

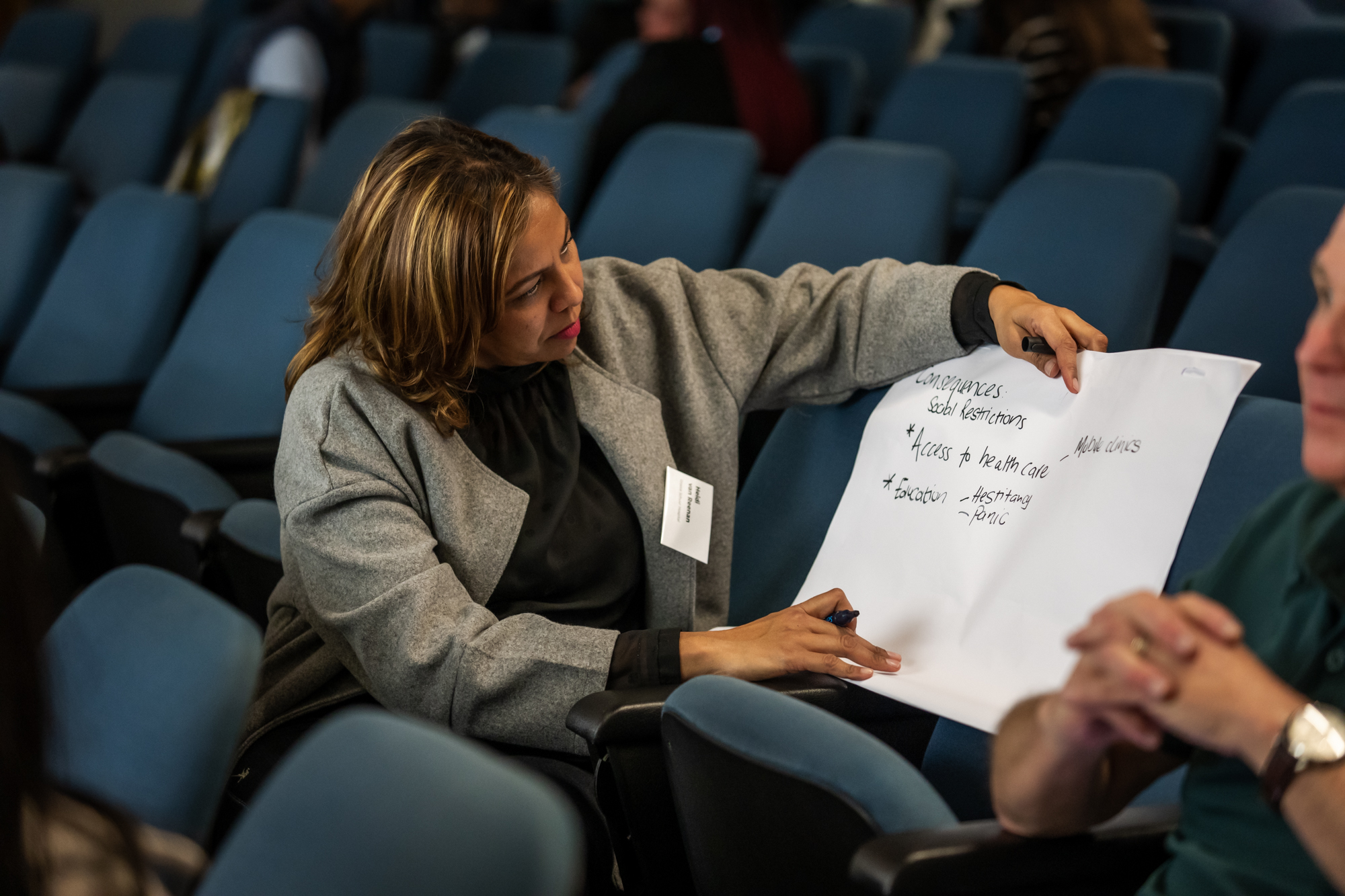

Learners deep in discussion during an antimicrobial resistance workshop in Khayelitsha, South Africa.

“Many people where I’m from are dying from AMR without knowing that it is AMR.”

The first time Thandokazi Njamela, a community activist in Khayelitsha, South Africa, saw the impact of antimicrobial resistance was in her own home. But she didn’t immediately understand it.

Njamela grew up in a three-room shack made of corrugated metal with 12 other people in Khayelitsha, a township about 30 kilometres outside Cape Town. An aunt she lived with became repeatedly sick with HIV until she eventually passed away. When another aunt also fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) and HIV, Njamela’s grandmother stepped in to care for her and became infected and repeatedly sick too.

Through community activism many years later, Njamela finally learned about drug-resistant TB – and later antimicrobial resistance more broadly – and connected it with her family’s experience.

South Africa is among the most impacted globally by antimicrobial resistance. For example, it has one of the highest burdens of drug-resistant TB on the African continent. More people die from antimicrobial resistance in South Africa than from self-harm, interpersonal violence or transport injuries.

Khayelitsha, which means “new home”, has a population of around two million in an area intended for 200,000. While there is a mix of socio-economic classes in Khayelitsha, more than half of its population lives in informal housing.

There’s not enough data on the state of antimicrobial resistance in Khayelitsha. Where data does exist, it’s focused on hospitals, leaving a large gap on the community impact.

It’s crucial that people with lived experience of antimicrobial resistance are involved in getting a complete picture of the problem and developing potential solutions. That’s why we’re funding three teams who are engaging communities in Khayelitsha to meaningfully involve them in research on antimicrobial resistance. Through creative and educational workshops, they aim to empower residents to learn more about antimicrobial resistance and contextualise their experiences.

Eh!woza is an organisation based in Cape Town, South Africa, working at the intersection of science communication, youth advocacy, community engagement and skills development. They aim to merge the science of disease with its social impact. Tasha Koch is the co-founder and co-director of Eh!woza.

PROTEA (Power Relations in the Optimisation of Therapies and Equity in Access) focuses on conducting intersectional research in antimicrobial resistance in India and South Africa. Associate Professor Esmita Charani leads the project at the University of Cape Town, with support from a Wellcome Career Development Award.

CAMO-Net (Centres for Antimicrobial Optimisation Network) is a research collaboration between several institutions around the world. They aim to help address antimicrobial resistance through contextually relevant interventions and practices. Charani is the co-principal investigator of the South Africa hub of CAMO-Net, together with Professor Marc Mendelson.

All three of these projects are supported by Wellcome and are collaborating to engage communities in Khayelitsha, South Africa. This work explores the real-world impact of antimicrobial resistance and empowers communities to demand action from the government.

“We want to understand what experiences people have had with AMR and what social factors people are associating with it,” explains Tasha Koch, Eh!woza’s co-founder and co-director. “[We want] to build up to thinking about contextually relevant solutions for AMR.”

Communities like Njamela’s have a wealth of knowledge about the challenges of dealing with the drug-resistant infections caused by antimicrobial resistance.

Community-based knowledge is essential to better understand exactly how antimicrobial resistance impacts people in specific contexts. By improving understanding, researchers can be better equipped to develop interventions that work for the people who need them.

The community engagement work of Eh!woza and Associate Professor Esmita Charani from the University of Cape Town is still in its early days, but useful insights are already emerging.

Antimicrobial resistance is connected to complex social issues

In Khayelitsha, antimicrobial resistance intersects with many social issues. These include employment, sanitation, hygiene, access to clean water, gender, race and even climate change.

For example, while working with 22 communities in Khayelitsha, Njamela witnesses the links between employment and antimicrobial resistance.

“If you're told you have TB, you're home and not working for six months. Then you think you’re okay and don't finish treatment. So you go back to work, then you get sick again and you're sent home again,” she explains.

Gender plays a role in antimicrobial resistance as well. Men face stigma from seeking medical attention, while women are expected to be primary carers, which puts them at risk of contracting an infection.

“AMR is doing a lot of things to our community, but people aren’t understanding what is causing it,” says Njamela.

Awareness of antimicrobial resistance is necessary, but so is agency to act on it

Like Njamela, many people in Khayelitsha have experienced the consequences of antimicrobial resistance without fully understanding it. That’s why raising awareness about antimicrobial resistance is so important.

But it shouldn’t stop there. Communities themselves must also be empowered to act.

“Even raising awareness about AMR and antibiotic use is not going to help communities raise themselves out of the conditions in which they live,” explains Charani.

“And so concurrent to that [awareness-building], we also need to work with policymakers.”

Charani notes that policymakers and decision-makers are also vital members of communities – and researchers must engage with them too to affect change.

“We want to narrate the experiences of people and how their daily living is impacted by inequality and how that manifests into public health crises such as antibiotic resistance,” says Charani.

“It isn't just speaking to the community about antimicrobial resistance, so people know about it then we're all happy. It's about bringing people’s stories and experiences into the conversation to be able to influence policy and decision-making around the subject.”

Thandokazi Njamela, a community activist in Khayelitsha, South Africa, attends an antimicrobial resistance workshop organised by Eh!woza and Associate Professor Esmita Charani.

Learners during an antimicrobial resistance workshop in Khayelitsha, South Africa.

A participant thinking about antimicrobial resistance during a workshop.

A learner shooting footage during a creative documentary making workshop.

Learners participate in an antimicrobial resistance workshop.

A learner participating in a creative documentary making workshop organised by Eh!woza and Associate Professor Esmita Charani.

We must encourage empathy between different groups

Eh!woza workshops don't only focus on knowledge exchange between lived experience experts and researchers. They are also a space for different groups within communities to come together and discuss the challenges people face.

For example, the workshops included healthcare providers, which led to conversations on the delivery and reception of healthcare for patients dealing with drug-resistant infections.

“The people we spoke with hadn't considered the time pressures and resource limitations that healthcare workers are under,” says Charani.

This open discussion can lead to more empathy and an improved understanding of the perspectives of each group. All this encourages more meaningful conversations and potential collaborations to tackle the problem more effectively.

“When you go to a clinic and hear a nurse shouting at someone, ‘You were here last time, and you’re here again for the same thing!’ You end up not wanting to go to the clinic because the nurses will be rude to you,” says Njamela.

“But no one understands that, to them, it's exhausting to treat the same patient for the same thing that could have been prevented.”

One key way to change this global outlook is to act locally – and a community-led approach is critical to doing this effectively.

Eh!woza has worked in Khayelitsha for many years and cultivated a strong relationship with the local community. Having this infrastructure in place allows researchers to meaningfully involve communities in projects.

Researchers can consider the local context and needs of the community, then work with them at various stages of the project.

This approach is vital for more meaningful knowledge exchange between researchers and communities, which can lead to more impactful research. Eh!woza and Charani will continue to collaborate with Njamela and Khayelitsha’s communities to guide the direction of their research.

They plan to conduct more creative workshops and train community members to collect data to understand the intersectional issues around antimicrobial resistance. Eventually, Khayelitsha’s residents will also be part of designing effective and relevant interventions.

For Njamela, the workshops have already inspired her and others in her community to think of more effective ways to communicate with government leaders and demand action on antimicrobial resistance.

She says: “You can never do something for us without us.”

In South Africa, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) kills thousands of people every year. These Wellcome-funded research teams are working with local communities to better understand the impacts of AMR – and to develop interventions that work for the people who need them.